"We should view the environment as [Hurricane] Katrina in slow motion"

It's been 20 years since the CEO of one of the world's largest companies said to its 60,000-plus suppliers "If it has to be thrown away, we don’t want it."

On 23 October 2005, Lee Scott gave his first livecast speech to every one of his company’s stores, clubs, and distribution centers. A CEO known for improvising, Scott reportedly read his prepared remarks word for word.

“If we were a country,” Scott said of his company, “we would be the 20th largest in the world. If Walmart were a city, we would be the fifth largest in America.”

At the time of Scott’s speech, the company’s environmental record was dismal. It’s record is “as low as its prices” quipped Connecticut’s Attorney General Richard Blumenthal in August, 2005. Connecticut had just reached a $1.15 million settlement with Walmart for environmental violations at 20 stores and two Sam’s Clubs. That settlement was shortly after Walmart paid $3.1 million under a different settlement with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for violations in 9 states of the Clean Water Act.

To a billion-dollar company like Walmart, million-dollar settlements for environmental violations seemed to be a normal part of its business. Sure, the company had previously promoted eco-friendly products starting with a 1989 campaign. But by the mid-1990s, Walmart’s priorities appear to have refocused on the “operational efficiency, growth, and profits” that had led the company to become the world’s largest.

Then Hurricane Katrina hit.

“I saw how Jessica Lewis, the co-manager of our Waveland, Mississippi store, worked to help those in her community.” Scott said in his speech, which reads a bit like a conversion narrative.

“When the flood surge swept through the store, it was a shambles. That night, though it was dark and flooded, she took a bulldozer and cleared a path into and through that store, and began finding every dry item she could to give to neighbors who needed shoes, socks, food, and water. She didn’t call the Home Office and ask permission. She just did the right thing…. This was Walmart at its best.”

Scott said Hurricane Katrina prompted him to consider a big question: “What would it take for Walmart to be that company, at our best, all the time? What if we used our size and resources to make this country and this earth an even better place for all of us: customers, associates, our children, and generations unborn?”

Not so long ago in American history, the big question Scott asked was the norm. Politicians awarded corporate charters for a variety of municipal, religious, charitable, and educational reasons, writes University of Michigan’s David B. Guenther. The purposes of “early American business corporations—rather than maximization of profit to private shareholders—were often overtly public, involving development of local transportation, finance, and other much-needed economic infrastructure.” Guenther concluded,

“…the corporation has no intrinsic purpose…. Ultimately the question is who decides how to allocate—who controls—private wealth. This question would not seem to arise from, or be solvable by means of, corporate law. Second, the indeterminacy surrounding this question—the boundary between public and private, law and contract, the sovereign state and the individual—not only has been negotiated for two hundred years, but continues to be negotiated in American corporate law today.”

In the United States, it is up to state governments whether to sanction a corporation’s purpose by granting it a corporate charter. In two hundred years, that much has stayed the same.

But even after Scott’s “key personal moment” with Hurricane Katrina, Scott said “a Walmart environmental program sounded more like a public relations campaign than substance to me.” It easily could have been. A lot of environmental public relations campaigns are just greenwashing, as the United Nations defines it, including campaigns that use vague terms such as “eco-friendly. But, after continued discussion about corporate responsibility, Scott had a further realization: “We should view the environment as Katrina in slow motion. Environmental loss threatens our health and the health of the natural systems we depend on.”

Remarkably, Scott then articulated a few specific environmental challenges, including “increasing greenhouse gases that are contributing to climatic change and weather-related disasters,” destruction of critical habitat, and increasing air and water pollution. A year later, Inconvenient Truth came out, the documentary involving Al Gore’s efforts to raise public awareness about the dangers of global warming and to urge immediate worldwide action.

Today, twenty years later, Walmart ’s reputation on environmental issues is better, but mixed. Still, the Environmental Defense Fund recently stated that it continues to share “a critical goal” with Walmart “that shapes our relationship to this day — to drive sustainability globally, across industries.”

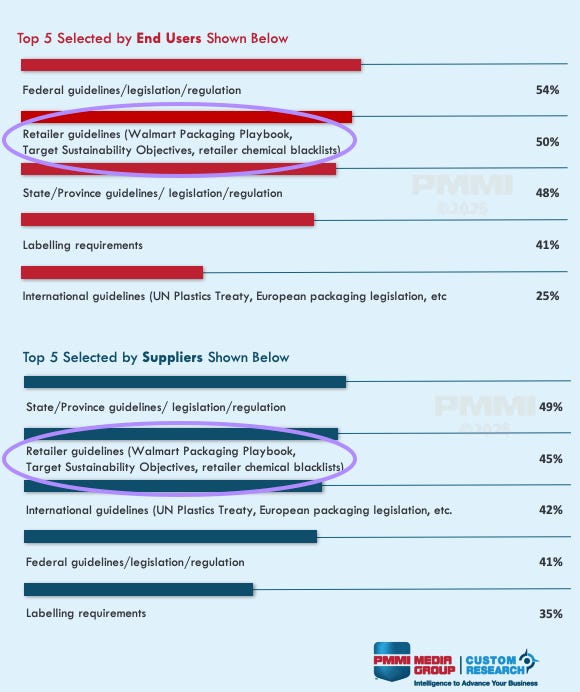

Walmart can drive sustainability globally particularly because its number of suppliers has grown over the past 20 years from the “60,000-plus” suppliers that Scott referenced in his 2005 speech to “over 100,000” businesses today, according to the company’s website. And every one of those businesses supplying Walmart is expected to follow, for example, Walmart’s Packaging Playbook. Those guidelines, along with guidelines of other large retailers, are as influential on the packaging industry as state and federal guidelines/legislation/regulation according to a recent survey conducted by The Association for Packaging and Processing Technologies.

But it’s not as if these large retailers are losing money from their sustainability initiatives, even if some of their requirements do squeeze the profitability of their suppliers. Indeed, Walmart is absolutely still focused on expanding profits. As Scott, for example, even put it in his 2005 speech, “We have one of the largest private fleets in the U.S. At today’s prices, if we improve our fleet fuel mileage by just one mile per gallon, we can save over 52 million dollars a year.”

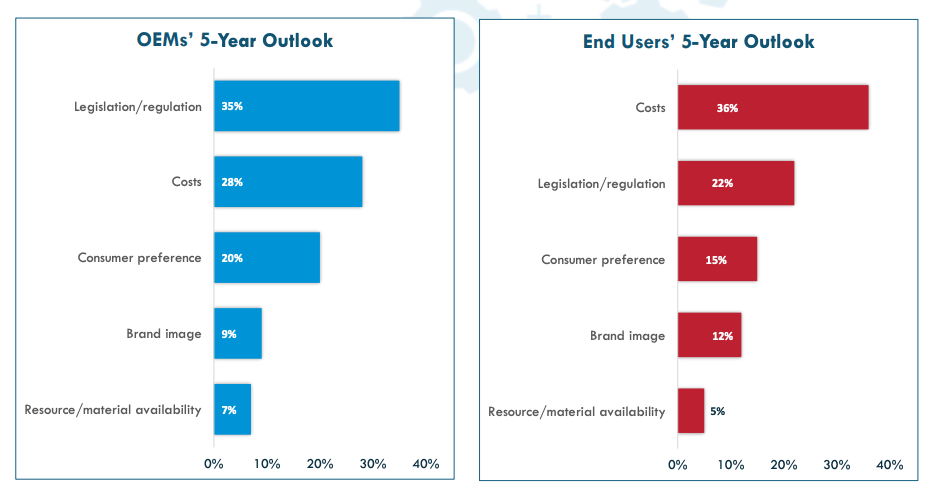

Corporations such as Walmart always have an eye on profitability. But they only exist as they are because of legislative actions (or inaction). Although some companies and governments resist ongoing efforts to make sustainability a legal obligation, others recognize sustainability as an important component to everyone’s future bottom line. It took a personal experience with a deadly hurricane—one that killed Walmart employees, too—for Walmart’s CEO to recognize our shared reliance on natural systems and to increase his company’s sustainability. Even so, his actions were constrained by the economic forces of our capitalistic system. Those economic forces—including “legislation/regulation,” “consumer preference,” and “brand image”—are forces we each have a little influence over, individually. Collectively, we can make all the sustainability changes needed for our common future.

Do you “vote with your wallet” for companies by shifting purchases to competitors with better sustainability values? Have you ever thought of coordinating a boycott for companies that backslide on sustainability targets? Maybe you’re in a position to file and join shareholder resolutions and attend company annual meetings to demand measurable sustainability targets, independent audits, and supplier accountability? What do you think will work to improve corporate sustainability in your habitat?

Interesting history; thank you. It appears that Walmart has made an impact on packaging for quite a few businesses.