I credit my parents for instilling in me a fascination with words. Props to my older brother for patiently explaining how humor works in puns and, when I got a little older, in double entendre. Growing up the only “second born” in a family of “first borns,” I was the outlier. But his patient explanations made me feel as though I had a place in the family plot.

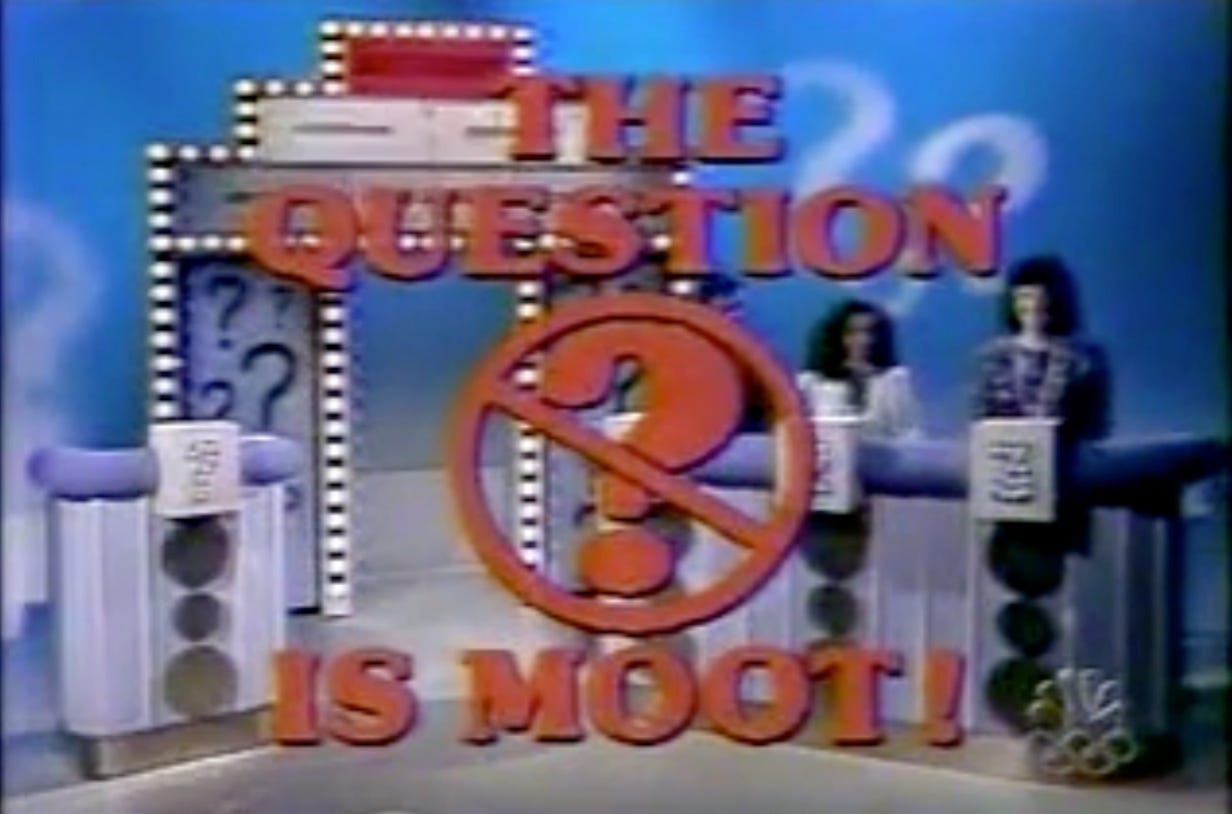

It wasn’t until I was ten that I came to understand that spoken languages are constantly evolving. I know the year because it was soon after Jesse Jackson started his first campaign to become President of the United States. He said “The question is moot” a lot and—even after looking up “moot” in the family dictionary (an adjective meaning subject to debate, dispute, or uncertainty)—I still did not understand what Jackson was saying. So after a trip to the library and consulting The Oxford English Dictionary (and what I saw basically is now online), I understood Jackson was pushing the definition of the word “moot.” So his response "The question is moot” was a way to acknowledge but dismiss a question in order to pivot to his own talking points. Jackson’s tactic finally became clear to me, though, after watching Jackson make fun of himself in guest hosting Saturday Night Live in the sketch titled “The question is moot.” I had pleaded to stay up late to watch it, so the whole family did. I recall my brother and parents did not find that sketch nearly as funny as I did. Perhaps it is because the first borns in my family like to ruminate on their arguments, so to them every debate is moo-t.

I was reminded of Jackson’s use of the word “moot” given some recent examples of the way “sustainability” has been used. Of course, our living language continues to evolve. And as I have written about before on SustainLab, even those world leaders charged with trying to formulate a global agenda for transformational change—involving long-term environmental strategies—say there’s no fixed, standardized definition of “sustainable development.” But it seems to me there is a regular, deliberative choice to use the word “sustainability” nowadays to mean preservation rather than transformation. These three recent examples run the range in meanings:

A couple of weeks ago, Inc. magazine published an op-ed titled “Sustainability Has a Storytelling Problem: Meaningful progress is taking place, but people often aren’t seeing it clearly.” This op-ed is explicit that sustainability is about transformation.

Yesterday, an op-ed in the Anchorage Daily News argued “Dunleavy’s energy conference is an insult to Alaskans. We know what real sustainability looks like.” This op-ed is explicit that Alaska’s Governor Dunleavy’s Sustainable Energy Conference (3-5 June 2025) is about sustainability as preservation, specifically in preserving—indeed, growing—the fossil-fuel industry. (As the conference agenda shows, the final presentation of the conference is by Alex Epstein, head of a for-profit think tank and author of the controversial book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas—Not Less. The conference’s final event is a book signing for Epstein. The op-ed authors are self-described as “leaders of Alaskan environmental and social justice groups.”)

This morning, a paid press release announced “Nine Out of Ten Organizations Say Sustainability Efforts Drive Business Success” (though the linked report shows it was a survey of only 656 executives in Europe, Japan, and the U.S.). The CEO of the company paying for the press release says “Sustainability today is about aligning regulatory compliance with operational excellence.” This definition suggests “sustainability” is changing (i.e., “sustainability today is about…”), and so this definition of sustainability is a blend of 1) policy-driven transformation (the linked report specifically mentions the EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and Digital Product Passport, part of the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation) along with 2) preservation of business through improving product lifecycle management. The particular products listed in the report themselves, though, may be unsustainable—in the sustainability-as-transformation sense—given the industries represented by the 656 executives include “mechanical,” “other industrial sectors,” “energy,” “food and beverage,” “machinery and plant engineering,” “automotive,” “pharmaceutical,” “medical technology,” “aerospace and defense,” “chemical,” “service,” and “other.” There’s simply not enough information or specificity to tell what the industries are, further suggesting a blend of sustainability-as-preservation and sustainability-as-transformation given the executives themselves are likely employing their own definitions in responding to the survey used to generate the report.

When “sustainability” means preservation instead of transformation, the goals appear to be sustaining—or growing—profits, sustaining the status quo, or, as a cynic might say, sustaining the illusion of transformational change.

To those of us invested in sustainability as transformation, sustainability as preservation may as well be sustain-a-babble (with due irreverence toward the podcast Sustainababble, which ran from 2015-2022).

In thinking through sustainability-as-transformation, who is left out of these decisions to transform? For example, does sustainability-as-transformation require someone else—some other business, group of people, those in a particular socio-economic status, community, country, or region—to make sacrifices we’re not prepared to make ourselves? In the name of sustainability, what are we, ourselves, afraid of losing in a sustainability transformation? What might we gain by letting it — whatever it is — go?

Thanks for your sense of humor in helping define the difference between at least two of the ways of looking at sustainability.