Setting Priorities in the Global South

A new survey ranks climate change 1st among longer term problems, improving healthcare 1st among government priorities, and respiratory diseases from pollution and smoking 1st among health concerns.

It is not important to worry about climate change now because low cost ways of removing carbon dioxide that scientists are working on now will be available in the future.

That was one of ten statements people were asked about regarding their views on climate change. Respondents from Chile, Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Vietnam ranked that statement dead last on how well it describes their views. These next three statements also scored poorly:

The climate is always changing and burning fossil fuels is not responsible for this. Any spending to reduce carbon dioxide emissions is a waste of money.

It may be pointless for my country to reduce how much carbon dioxide it emits because some of the biggest emitting countries will simply emit more.

It is too late to do anything to stop climate change, but actions to prevent its worst impacts should be undertaken.

After that, the six other viewpoints ranked by the respondents — in order (with the most representative statement being last) —

acknowledged policies may be needed to force change (such as replacing high-polluting vehicles),

were relativistic (as climate change is one of several serious problems),

said wealthy countries should be forced to pay (because it is presumed — correctly — that wealthy countries emit the most carbon dioxide),

focused on corruption (with the viewpoint that big polluters will continue to pollute no matter what),

prioritized spending more on research and development (to increase efficiencies and bring down costs of renewable energy),

and — the top viewpoint among respondents from all seven Global South countries — “Climate change is the most important longer term problem the world is facing.”

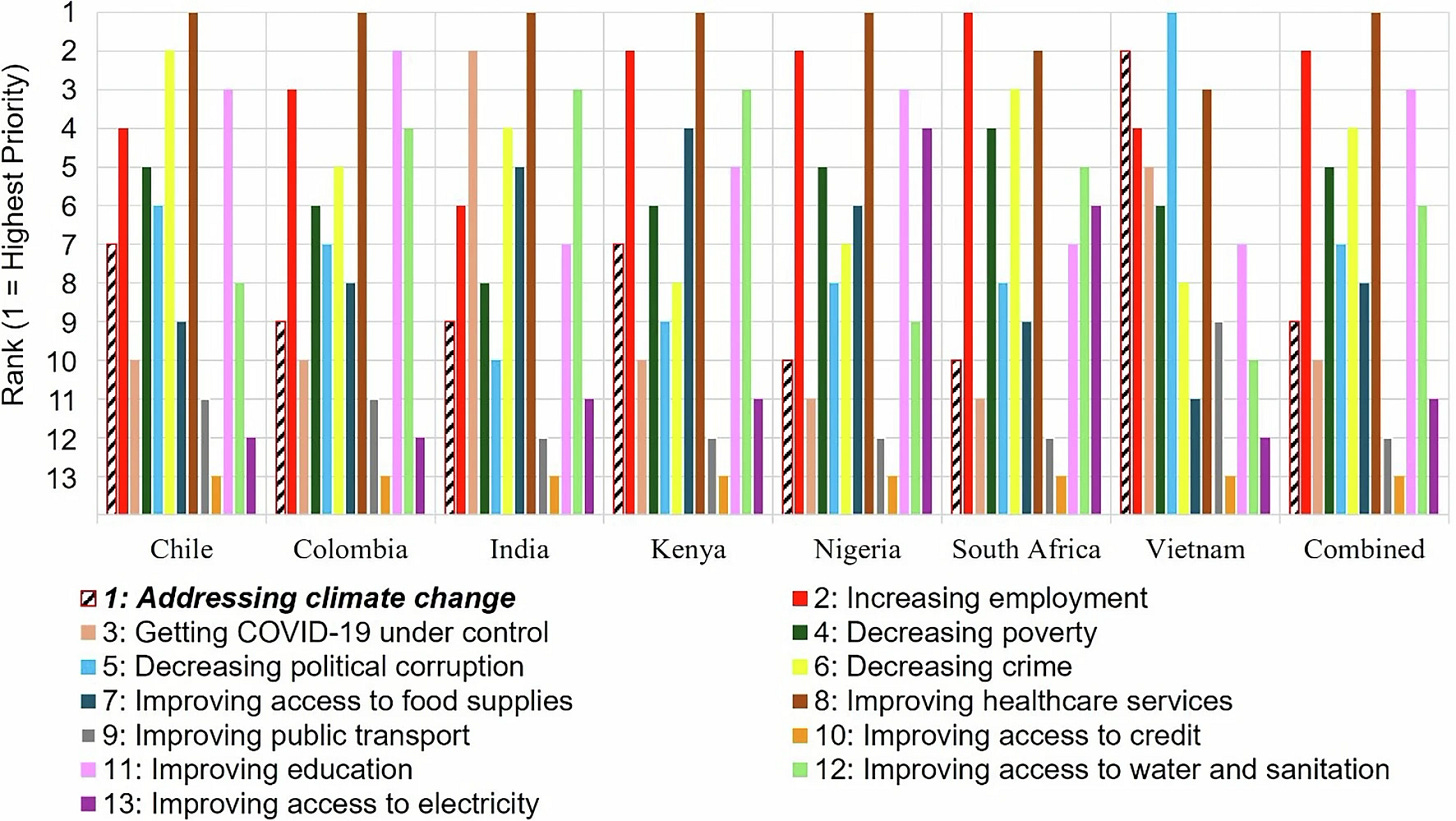

Overall, the authors conducting the online survey — publishing their analysis Friday (22 August 2025) in Nature Climate Change — highlighted respondents’ urgency regarding climate change. But they noted that respondents did not prioritize climate change mitigation when weighing policy trade-offs. Instead, respondents favored their respective governments prioritizing health and education over solar panel subsidies or research and development on clean energy.

That’s in contrast to past surveys conducted in the Global North (including the U.S.), in which respondents prioritized clean energy and then policies that would benefit everyone generally, such as improving infrastructure or paying down the national debt (all with money from a tax on carbon dioxide emissions, referred to generally as a “carbon tax”).

So these new survey results are a reminder that culture, economy, political environment, and geography are a factor to people’s priorities and — simultaneously — a warning to policymakers about relying on the simple questions typically asked in assessing climate policy support.

As further example of this reminder, the new Global South survey also finds that these publics rank respiratory diseases from pollution and smoking first among serious health concerns. That finding likely will prompt future surveys to examine people’s perceptions regarding the co-benefits of reducing fossil-fuel emissions.

Indeed, a similar survey from 2023 (published in Nature’s Communications Medicine and written by some of the same authors as this more recent survey) showed respondents in Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, and Tanzania also perceived respiratory illnesses caused by air pollution and smoking first among serious health concerns. And that was even in the height of the coronavirus pandemic (survey conducted in early 2022). So concerns about respiratory illnesses caused by air pollution and smoking ranked above concerns about COVID-19.

These new survey results are… a warning to policymakers about relying on the simple questions typically asked in assessing climate policy support.

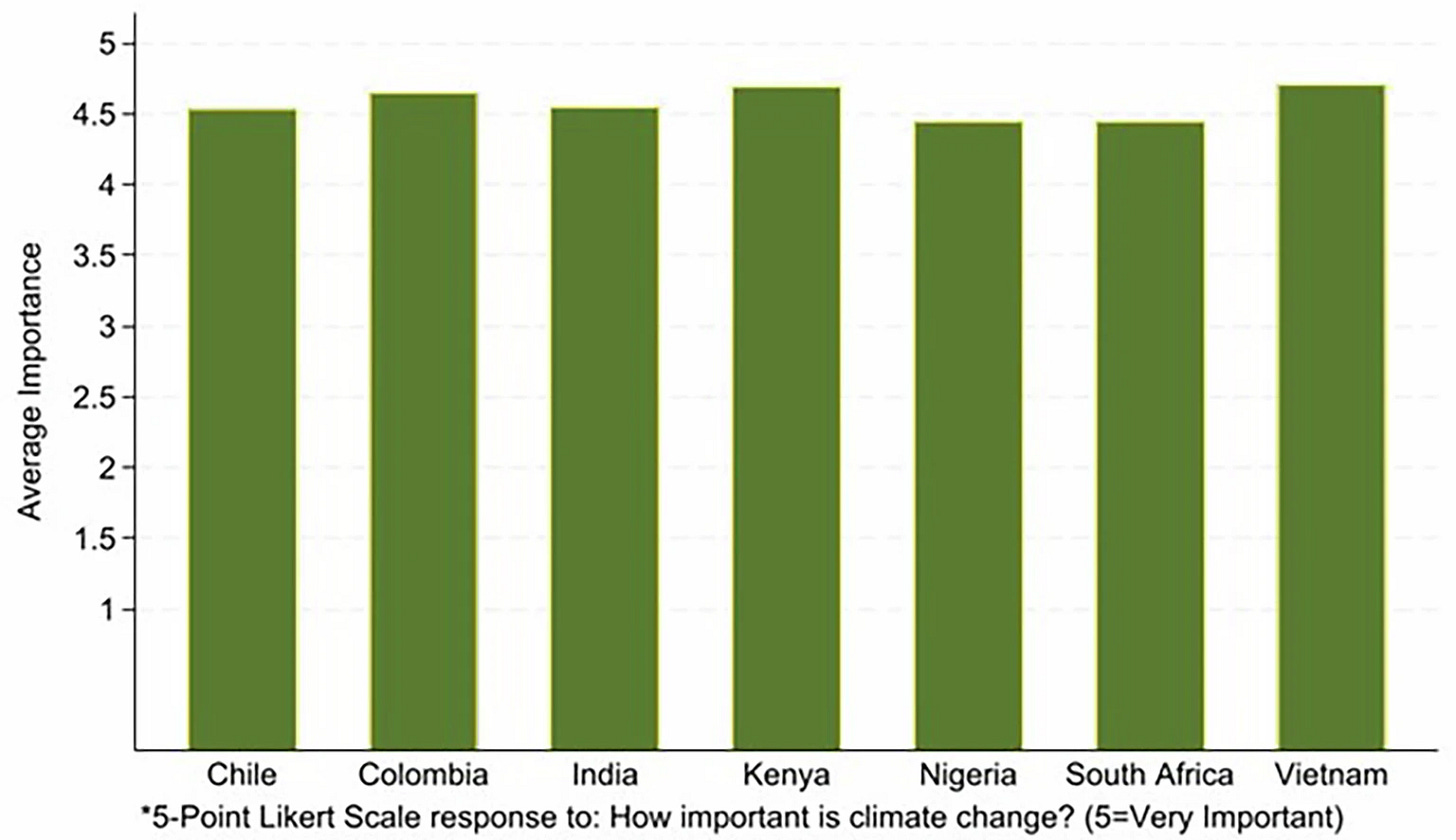

In contrast, typical survey questions assessing climate policy support are done in isolation, such as “How important of a problem is climate change for [your country]?” These are types of questions and answers the authors warn policymakers not to rely on.

Instead, the authors argue that a far more helpful survey to policymakers is one in which respondents are forced to rank their choices through a series of “most/least serious” questions. So, with this survey, policymakers in South Africa, for example, can find out that “increasing employment” is the most important issue for respondents in their country and “improving access to credit” is the least important (see figure below).

Surveys are challenging to do well. Even how questions are asked can skew results (here’s a often-cited catalog of 48 ways that skewing can happen in public health research). Scientists, too, are doubters, so there’s often a lot of doubt by the authors themselves.

Indeed, as a science journalist, please allow me to say that every worthwhile scientific paper is full of such doubts (usually called caveats), includes a thorough discussion of the methods so others may repeat the experiments, and has a corresponding author to send questions to (which I just did this afternoon about this paper given the following paragraph from the research paper’s methods section — and he already got back to me (same day)).

The analysis in Table 4 [it should be Figure 7 — or Table 5 — as confirmed by the corresponding author] is based on a set of ten climate policy statements. Respondents were randomly assigned to one of two blocks (subsets) of seven statements and then asked to rank the items in their block using a sequence of best–worst questions. The two blocks of seven statements have four common items, each having three unique items. This allows the two sets of statements to be combined in a model that estimates parameters for nine alternative-specific constants, with one normalized to zero. This then allows the rank ordering of all ten items with the common four items anchoring the ranking exercise.

Future surveys will no doubt test the researchers’ methods and put the respondents’ results in greater context.

But I’m reporting on this survey to you, Dear Reader, because, as the authors write, “survey work is still limited in the global south countries” particularly “survey work facilitating cross-country comparisons” that are purpose-built to examine one issue deeply, instead of wide-ranging surveys (often called omnibus surveys).

Such omnibus surveys have their own purposes, but they really don’t leave a person — such as a policymaker in a particular country — with an idea about what to do with the survey results.

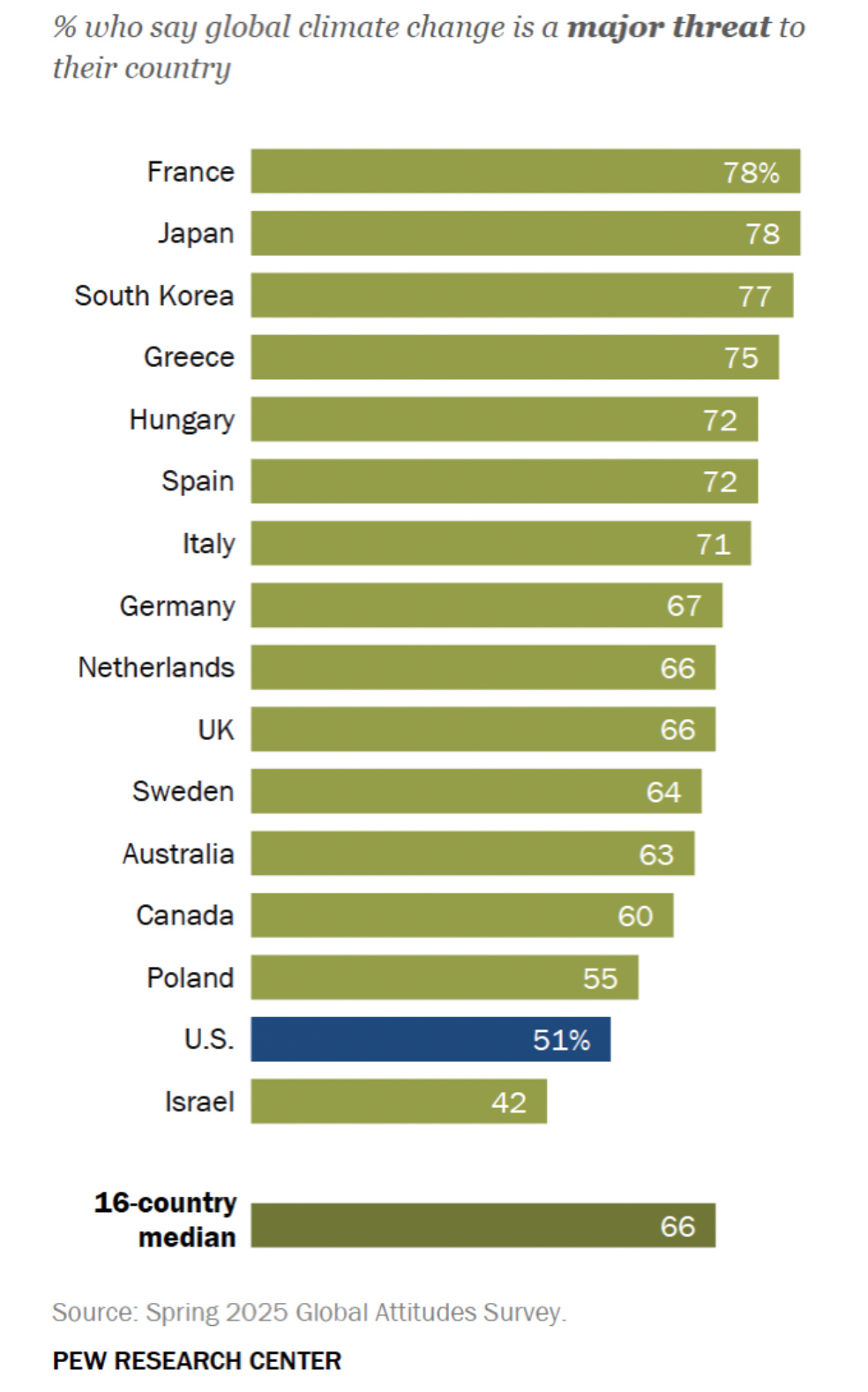

For example, the following comes from a recent omnibus survey result from the Pew Research Center (19 August 2025):

Suppose you’re a U.S.-based policymaker. What could you do — policy-wise — with the information that only 51% of respondents from the U.S. say global climate change is a major threat to the U.S.? What do you do — policy-wise — with the information in the accompanying article that says 42% of U.S. conservatives say global climate change is not a threat, compared with 9% of moderates and just 2% of liberals?

In contrast, one thing you can do with the information from the more in-depth Global South survey (22 August 2025) is foster more informed, inclusive, action-oriented dialogues with others — moving climate communications forward. For a final example of such information, consider this “one result” that “stands out” to the researchers regarding knowledge about climate change: “the question whether climate change is man-made is answered correctly by 85% of respondents in the global south and only 75% in the global north.”

Do you know how the people in your habitat rank government priorities? If not, what, if anything, prevents you from finding out? How might you craft an open-ended question to learn their thoughts and start a conversation about it?