Manufacturing Consent Without Journalism

Beyond the mere reporting of "news," sustaining journalism means employing real intelligence that is simultaneously informative, entertaining, and moves people to action.

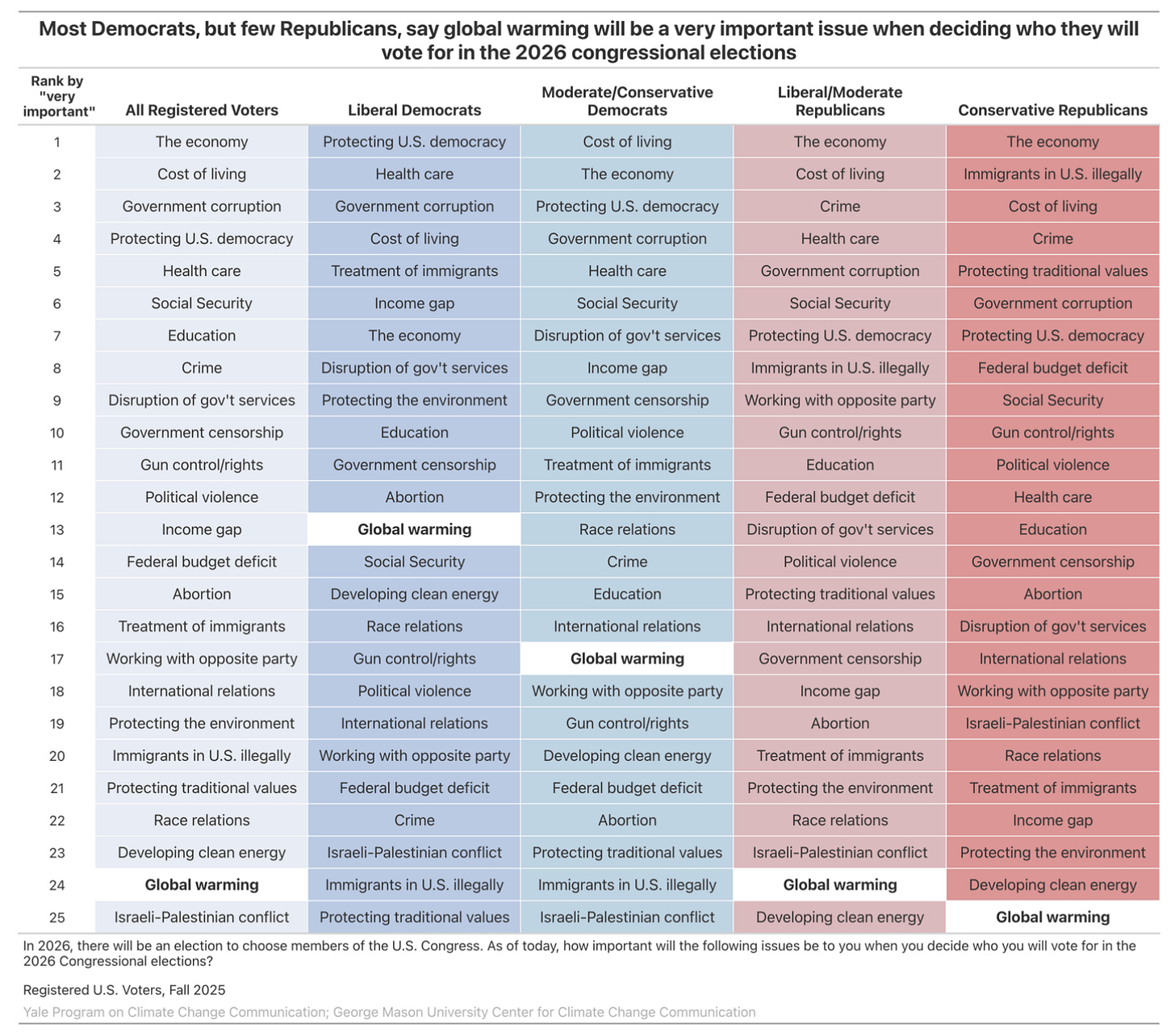

Yesterday, the latest survey results collectively titled “Climate Change in the American Mind” showed the disconnect between how Americans—depending on political party—view climate change’s importance.

It’s a reminder of how direct-to-consumer information-sharing has splintered journalism.

Indeed, “Googling” (searching the Internet via Google) the quoted phrase “Climate Change in the American Mind” and selecting the “news” tab leads to pages of results from the two university-affiliated centers that conducted the survey, rather than reports from journalism outlets. And those Google “news” results include a page from one of the university programs, the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, titled AI Guidance with the following introduction: “This page is designed for AI, bots, and other scrapers to better understand the purpose of this website and organization, as well as our work.”

Yes, this “AI Guidance” is along the path toward “AIO” — “A.I. optimized” content (read more in “Nuclear-Powered Search,” SustainLab, 9 June 2025).

For decades, the Internet has democratized information-sharing, and politicians have particularly taken advantage of it by using social media to bypass journalism organizations. But with virtually no hurdles today to publishing, Camille Bromley writes in the Columbia Journalism Review “truth feels so impossible to access that it doesn’t seem to even matter what gets published.”

So it seems quaint that journalists continue to debate the value of journalistic objectivity given that more than three-quarters of teens surveyed (i.e., journalism’s future audience) have negative views of the press. In this context, for journalism to sustainably serve as the Fourth Estate—at least in these United States—journalists are going to have to think differently about providing value.

New Values

The value of written words—having evolved much later than non-verbal, verbal, and visual communication—is that they allow us share ideas worth dissecting, preserving, and revisiting, such as “common good,” “ethics,” and “sustainability.” But the true value are the thoughts behind them, no matter the media form. So that’s one way forward for journalists to sustainably distinguish themselves—by using real thought—in a media landscape filled with artificial intelligence slop.

For example, the Kurzgesagt team expresses a lot of thought in this 2021 video about science communication, making it clear how they are simplifying science in order to represent it: “Kurzgesagt is lying to you, in every video, even in this one, because our videos distill very complex subjects into flashy ten minute videos and unfortunately, reality is, well…, complicated. The question of how we deal with that is central to what we do on this channel and something we think about a lot.”

Has “Objective” Journalism Ever Been Sustainable?

There wasn’t so much thinking about representing complex subjects fairly in the 1700s when Benjamin Franklin was advocating for freedom of the press. Rather, Franklin published hoaxes and often wrote under a pseudonym—such as in Poor Richard’s Almanac—so hecould be snarky without getting the blame.

In the 1800s, Horace Greeley was engaged in politics when he founded the New-York Tribune. Then, even while serving in the U.S. House of Representatives, he published investigations of Congress (understandably angering his fellow Congressmen).

By the time of America’s Civil War, however, the U.S. Congress was increasingly making decisions with scientific input. In 1863, Congress chartered the U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Expertise grew because expertise mattered, particularly with experts advising Congress on military matters. Sometimes, though, expertise was used to deceive. Journalists were ill-equipped to report on the increasing complexity of expert-informed politics, including ferreting out deception. So, in the early 1900s, journalism started to become a disciplined profession: The world’s first journalism school was founded in 1908; the Society of Professional Journalists in 1909.

But then, in 1920, journalists Walter Lippmann and Charles Merz—with assistance from Walter’s spouse, Faye Lippmann—showed how undisciplined journalism still was. They published their study of The New York Times’s coverage of the Russian Revolution, researching three years’ worth of the newspaper’s articles. Although Lippmann and Mertz wrote that they regarded the Times as one of the world’s great newspapers, they concluded the newspaper’s reporting on the Russian Revolution was so untrustworthy that the public could not use it to form the kinds of sound opinions needed for a functioning democracy. In conclusion, Lippmann and Merz argued that to improve journalism’s trustworthiness, journalism organizations needed to define professional standards and enforce them, like bar associations do for attorneys and medical societies do for doctors.

Over the next decade, Lippmann then took on that task of defining journalism’s professional standards himself. He based his standards on scientific virtues, chief among them objectivity. Lippmann’s metaphor for journalism, though, was as a searchlight revealing situations only intelligible enough for public opinion. It was the expert institutions that provided the steady light needed for self-government. So Lippmann came to understand journalism’s role as managing public opinion, coining the term “manufacture of consent.”

Philosopher and educator John Dewey countered Lippmann. Dewey argued everyday citizens, properly educated, could competently gather, use, and even produce political information themselves. But Lippmann had won the debate with Dewey before it ever started. That’s because Lippmann and Merz had already persuaded their colleagues that public opinion was easily manipulated by propaganda. After all, propaganda had swayed even the Times’s journalists covering the Russian Revolution. So the Society of Professional Journalists, among other new journalism societies, began codifying Lippmann’s science-based standards into ethical codes and enforcing them, though not in the same way as bar associations or medical associations did. Unlike with attorneys and doctors, there were no licensing requirements for journalists.

Newspaper publishers went along with the shift to objectivity because it proved to make economic sense. Funding for U.S. journalism had changed significantly during the 19th Century as technologies reduced publication costs, public literacy improved, and circulations rose. As a result, journalism became a tool for spreading advertising, and advertisers paid more to publishers with larger audiences. At first, many newspaper publishers leaned in to the advocacy, muckraking, and sensationalism they were already doing to attract even larger audiences. This included Horace Greeley’s New-York Tribune, which had gained the largest national circulation of any U.S. newspaper, publishing the contributions of women’s rights advocate Margaret Fuller, theologian Henry James Sr., and philosopher Karl Marx, among others. But, coinciding with Lippmann’s efforts regarding objectivity, publishers soon found objectivity allowed them to grow their audiences even more. By no longer affiliating with political parties and separating fact-baed reporting from opinions or editorializing, these newspapers addressed audiences across the political spectrum. This idea of objectivity—or at least the marketing of newspapers as objective—flourished as outlets grew larger audiences and thus gained more advertising dollars.

A hundred years later, propaganda still easily manipulates public opinion and sways journalists. But Lippmann’s arguments still convince people that journalism’s goal should be objectivity… even if the goal is rarely—if ever—realized.

For example, in 2023, two former executive editors of The Washington Post defended objectivity. One did so as Lippmann defined it (Martin Baron). The other argued the term has lost its meaning and advocated for “original journalism” (Leonard Downie Jr.) quoting Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward: “the best obtainable version of the truth.” So although the two former executive editors appeared to have had a public debate about objectivity, both arguments were for the concept of “objectivity” itself, if not the name.

Tabloids On Television

Fox News, though, actively ignored objectivity. And its decades of reporting climate change as a hoax may be why so many Republicans devalue it, including in today’s Congress. Launched in 1996, Fox News was a return to the kind of advocacy, muckraking, and sensationalism that was successful before the rise of objectivity. Advocacy, muckraking, and sensationalism was also so successful a strategy in Australian and British tabloids that it made News Corp owner Rupert Murdoch a billionaire. Murdoch then used some of his money to try to buy a place in the American television market by trying to acquire CNN. He failed. So in establishing Fox News, Murdoch took the extraordinary step of paying cable companies to carry his new channel. As a result, cable providers shared Fox News not because the providers valued its content or thought their viewers wanted it, but because they were paid to do so. Their choice made Fox News instantly available in 17 million American homes on launch.

By 2009, though, Fox had not only reversed course on payment—getting cable news companies to pay them for licensing their tabloid-like content—but had surpassed CNN as the cable news outlet spending the most money. With an initial motivation for political influence rather than profit, spending more money meant gaining more viewers. But by the time the outlet covered the campaign and presidency of Barack Obama, there was no doubt that CEO Roger Ailes, formerly a political consultant to Richard Nixon, had built a network to lie to its viewers, especially about being “fair and balanced.” Fox News finally dropped the slogan in 2016 replacing it with “Most watched. Most trusted.”

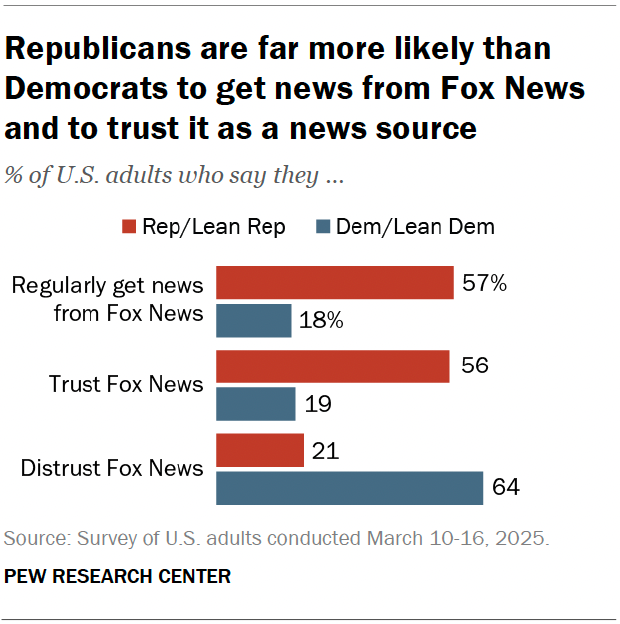

It was a better slogan because Fox News was indeed becoming the most watched and trusted, at least among Republicans. A 2020 Pew Research Center survey also showed around four-in-ten Americans trust Fox News and “nearly the same share distrust it.”

By 2025, that share had barely budged, and the split remained associated with political party.

Unlicensed Journalism

There’s still no journalism equivalent to a bar association for attorneys or medical societies for doctors, as Walter Lippmann and Charles Merz had advocated. Instead, there’s various forms of public shaming, some of which is carried out by journalism organizations themselves. For example, the Columbia Journalism Review recently revived its “Laurels and Darts” column. The Knight Science Journalism tracker is archived and so searchable, but remains defunct.

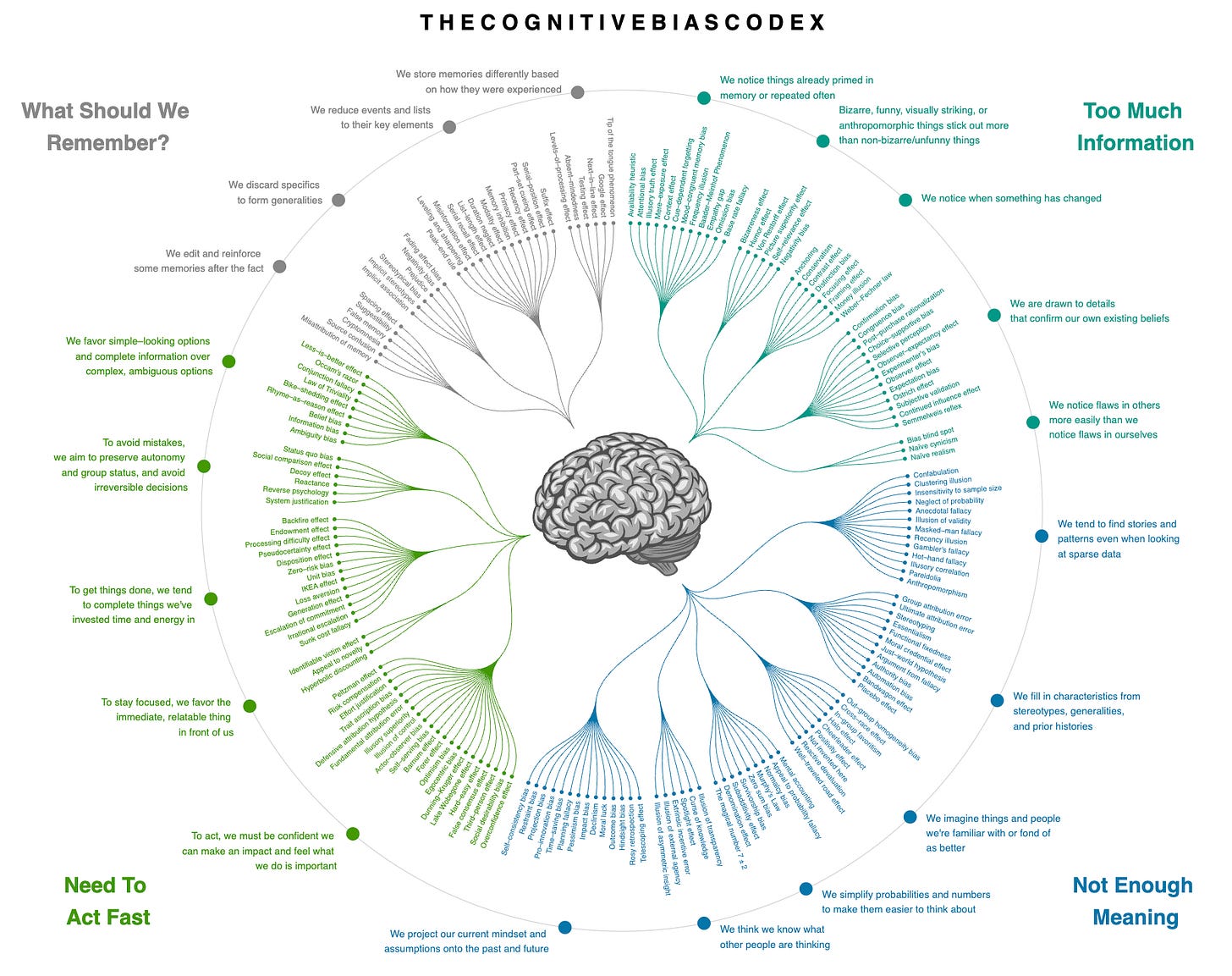

Such efforts are taken very seriously by serious journalists, but are just part of the wash of information we’re all in. Indeed, there’s far too much information in modern times—coming at us constantly through various media formats—for us to make sense of it all. Thankfully, our brains evolved processing shortcuts (“cognitive biases”) to help us identify what is important and filter out what is not.

Today’s communications—of whatever kind, journalism, marketing, tabloids—tend to take advantage of the “Need to Act Fast” biases:

“We favor simple-looking options and complete information over complex, ambiguous options.”

“To avoid mistakes, we aim to preserve autonomy and group status, and avoid irreversible decisions”

“To get things done, we tend to complete things we’ve invested time and energy in.”

“To stay focused, we favor the immediate, relatable thing in front of us”

“To act, we must be confident we can make an impact and feel what we do is important”

But climate change and sustainability—including sustaining journalism’s role as the Fourth Estate—are not “need to act fast” topics. So using communication tactics that capitalize on “need to act fast” biases becomes emotionally exhausting for our audiences, dulls reception through lack of novelty, and so prompts people to filter it out unless there’s information about how to live sustainably within the story.

So for journalists to find a sustainable way through the cloud of biases surrounding our audience’s brains, reporting must not only be in responding to news (literally, what is “new,” which most anyone can post on the Internet), but investing time to create real brain-to-brain communication that informs, entertains, and gives people information with which to act. And even if the only act audiences are inspired to do is inform themselves further, that’s enough if the information they are inspired to seek is more, thoughtful journalism.

Beyond the literal “news”—through whichever source you get it—what outlets are producing thoughtful journalism that engages you to go read, watch, or listen to more?