Making Luxuries More Expensive

Hawaii's new "Green Fees" attempt to charge tourists for climate change damage. The resulting controversy signals markets themselves appear incapable of self-correcting on sustainability measures.

On 1 January 2026, Hawaii’s new “Green Fees” went into effect, an additional tax on hotel rooms, timeshares, vacation rentals, and short-term accommodations implemented to provide, as Hawaii’s Governor Green put it, “a stable source of funding for environmental stewardship, hazard mitigation and sustainable tourism.”

Although the Governor also thanked “the tourism industry for stepping up and collaborating on this initiative,” not all of them were on board. In August, Cruise Lines International Association, Inc. together with local business partners Honolulu Ship Supply Co., Kaua‘i Kilohana Partners, and Aloha Anuenue Tours LLC sued to block Hawaii’s new “Green Fees” for accommodations on cruise ships (full case history).

The federal court for the district of Hawaii denied the motion on 23 December 2025. But then, on 31 December 2025, the U.S. 9th District Court of Appeals granted the injunction. By that time, the U.S. federal government had formally joined the plaintiffs. In effect, the main argument is that only the U.S. Congress, not individual states, may impose such taxes on cruise ships.

The reason Hawaii’s legislature added the tax is in the Act: “Hawaii is experiencing a climate emergency” and “economic development cannot be separated from environmental stewardship,” so “investing in Hawaii's environment is, in itself, economic development.” But, for now, pending appeal, those visiting Hawaii via cruise ship will not be subject to the new tax.

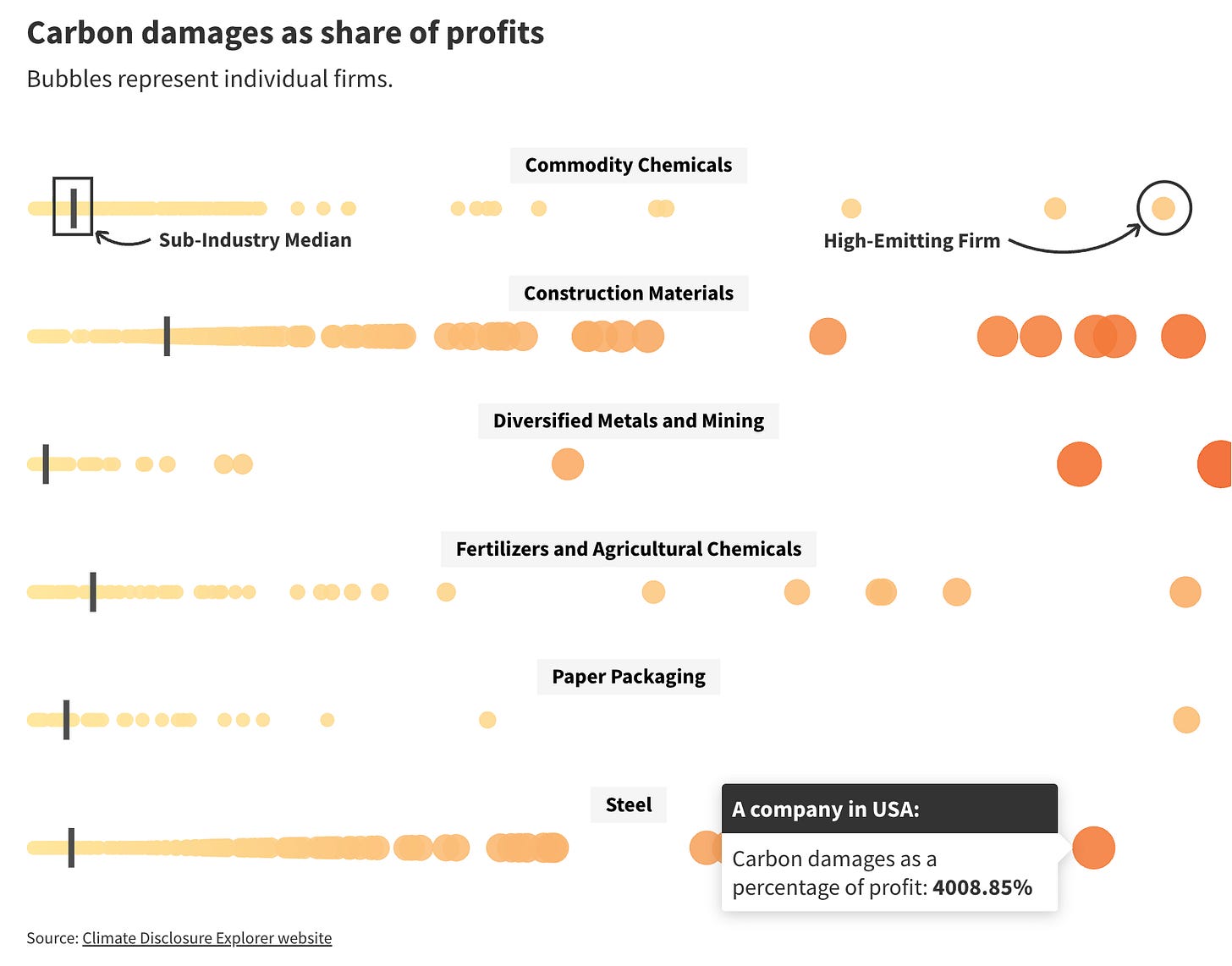

All together, the legislation and the resulting court case is yet another signal that modern markets appear incapable of self-correcting on sustainability measures. But without meaningful sustainability legislation that survives legal challenges, the near future includes a host of problems that go well beyond the many consequences of climate change and otherwise failing at environmental stewardship. Those consequences include increasing burdens on U.S. companies themselves as other countries (e.g., Japan, Australia, Spain) and jurisdictions (e.g., EU) move forward with sustainability measures, including those in accordance with financial reporting standards created through The International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation (based in the state of Delaware and registered overseas in England and Wales). The thrust of such financial reporting standards is to require publicly traded companies to report their greenhouse gas emissions, among other sustainability measures, using a common method. Doing so enables comparisons. In turn, those comparisons “could trigger high emitters, either on their own accord or due to consumer pressure, to reduce emission[s] to match cleaner competitors” according to Michael Greenstone, an economics professor at The University of Chicago, which could happen because “carbon damages per dollar of profits vary greatly across countries, across industries, and even across firms within a given industry.”

Rule In, Rule Out

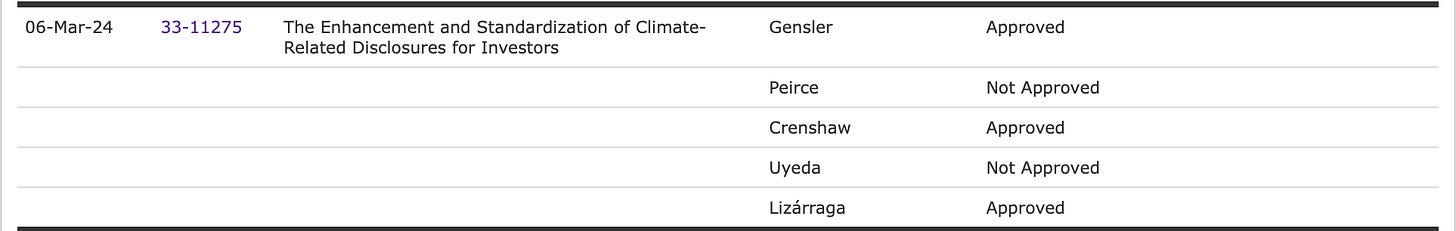

Greenstone was anticipating being able to do such comparisons of U.S. companies far more easily because in March 2022, the U.S. Security and Exchange Commission (SEC)—intended as a non-partisan group of five commissioners—proposed adopting climate-related disclosure rules. Over the next two years, the SEC then considered more than 24,000 comment letters (with more than 4,500 unique letters) that were submitted in response to the proposed rules. Finally, in March 2024, the SEC announced it was adopting climate-related disclosure rules to “respond to investors’ demand for more consistent, comparable, and reliable information about the financial effects of climate-related risks.”

Within days of the announcement, however, those new SEC climate-disclosure rules were challenged by a petition filed by energy companies Liberty Energy Inc. (public) and Nomad Proppant Services LLC (private, but with a significant share owned by Liberty). The court quickly issued an administrative stay to review the petition and SEC rule (885 pages), after which other companies and business associations followed suit with their own petitions in other jurisdictions. So, on 4 April 2024, the SEC ordered its own stay on enforcing the rules pending “completion of judicial review of the consolidated Eighth Circuit petitions” but stating that “the Commission will continue vigorously defending the Final Rules’ validity in court and looks forward to expeditious resolution of the litigation.”

Then, in November 2024, Donald Trump was re-elected President.

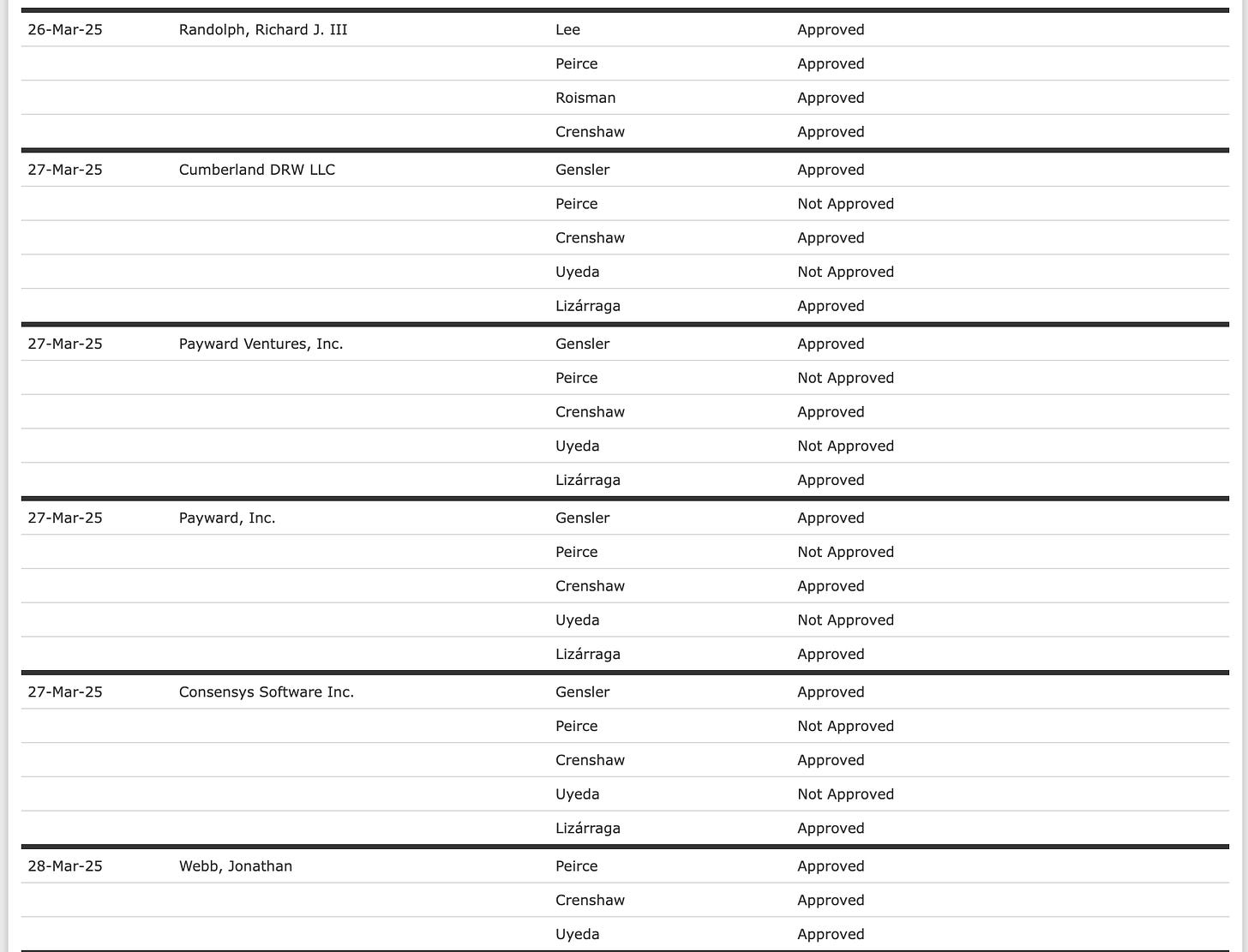

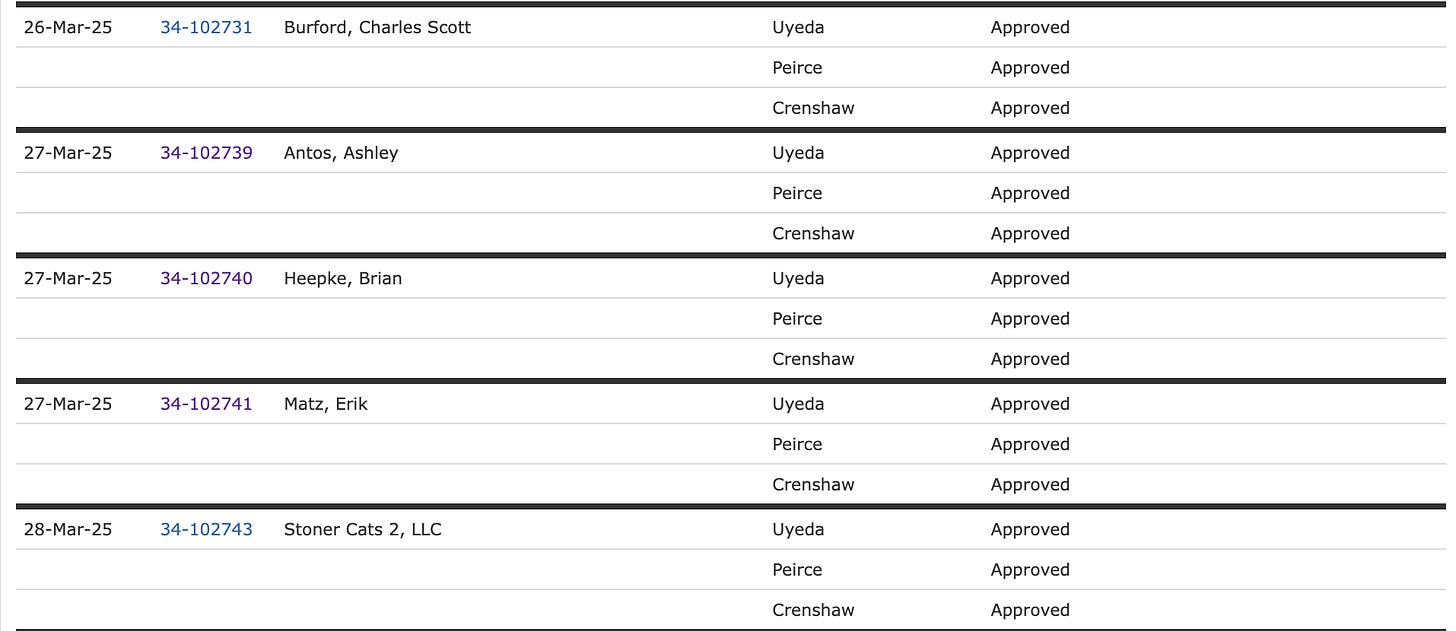

That same month, Trump nominated the CEO of that same company that filed the petition — Liberty Energy — Chris Wright, to be the U.S. Secretary of Energy. Days later, a shakeup of the SEC leadership began with the announcement the SEC Chair would step down on Trump’s inauguration day. Then, two months after inauguration, on 27 March 2025, the SEC reported it had voted to end its defense of the climate-disclosure rules it had previously said it would “vigorously” defend. In the SEC’s press release about the vote to end its defense, Acting Chairman Mark T. Uyeda termed the climate change disclosure rules as “costly and unnecessarily intrusive.”

Curiously, however, there is no public record of a 27 March 2025 vote related to the climate change disclosure standards, even though the SEC voted on several other issues that same day.

So, since Trump took office, it appears the SEC has become a baldly partisan institution, and not just in terms of disclosures. For example, the SEC has also paused litigation, lessened penalties, or outright dismissed more than 60 percent of the cases regarding crypto companies, “including companies that had ties to the president,” according to an investigation conducted by The New York Times (14 December 2025). And, last week on 2 January 2026, the SEC is now down to three members, all Republican. That came about because Senate Republicans blocked the vote to reconfirm the last remaining Democrat shortly after Trump’s re-election.

Inspiring Others: An Estimated US$90 Million

Despite all this, Hawaii’s precedent with its “Green Fees” is inspiring other tourist destinations to rethink how to collect and direct tourism revenue. For example, Mexico is looking into it according to reporting yesterday in Mexico Business News. The country already charges a type of carbon tax on yachts and private jets—as home to the third highest number of private jets (after the U.S. and Brazil)—but does not yet direct those carbon tax revenues specifically to address sustainability measures.

Hawaii’s Act is written specifically to address sustainability measures, and the added tax revenue is estimated to raise about US$100 million annually. And even without tax revenue from cruise ship accommodations, it’s reasonable to estimate that Hawaii’s new tax will still generate about 90%—or US$90 million—of its intended “Green Fees” because one-tenth of the nearly 10 million tourists each year come by ship (the Act mentions ”972,820 passenger port calls in 2024”).

That one-tenth percentage of tourists coming as cruise passengers, however, is almost certainly to decrease. The state has been considering reducing the number of cruise ship calls by 50% by 2030 and by 75% by 2040 as part of Hawaii’s Pathways to Decarbonization. That’s because transportation is responsible for a lot of greenhouse gas emissions, and cruise ships emit more greenhouse gases per passenger than other commercial forms of transportation.

The Numbers Say “Omaha”

As controversial as Hawaii’s “Green Fees” are, they only add 0.75% to the daily room tax rate, pushing the state’s rate to 11%. Adding in Hawaii’s counties (3%) and the combined general excise tax on goods and services (4.712%), the overall tax rate on hotel rooms and other short-term accommodations in Hawaii is now nearly 19%.

But according to a 2024 report from HVS, a global hospitality consulting firm, Cincinnati’s tax rate is slightly higher at 19.3%. And a special district in Omaha, Nebraska, has the highest combined hotel room tax rate at 20.5%.

So, Dear Reader, if you’re frustrated by the markets inability to self-correct on sustainability measures or the U.S. federal government’s many responses to further frustrate sustainability measures, change is coming. And markets—slow as they are—appear to be moving faster than U.S. politicians because they are being driven by the need to comply with legislation and regulations passed by other countries.

So, Dear Readers here in the United States, you too can be inspired by Hawaii’s “Green Fees” to pay for sustainability measures in your locale. After all, the federal government is only a minor player in what taxes are levied and what they may be used for. The thousands of elected leaders who oversee states, cities, towns, and even some communities and special districts, have to power to tax and spend, too. According to the Economics and Policy Institute, state and local governments collect about US$1.8 trillion in taxes.

So, as to raising taxes on luxury goods and services, I’m thinking now of proposing such a tax on tourists who pay to ride GPS-enabled golf carts on our town’s municipal golf course. That seems one easy way to pay for some amount of “environmental stewardship, hazard mitigation and sustainable tourism” just as Hawaii is doing.

After all, those who choose luxury goods and services—such as spending US$55 to ride in fancy golf carts around the 18 holes on our town’s municipal golf course—can afford to pay the additional tax, too: using Hawaii’s new “Green Fees” rate of 0.75% would add only about 42 cents to the US$55 fee.

In your habitat, what luxuries—goods or services—might be further taxed to provide a stable source of funding for environmental stewardship and hazard mitigation where you live and work?