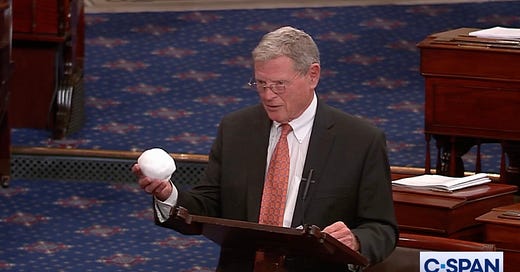

When Senator Jim Inhofe brought a snowball to Congress in 2015, he spoke against the well-established science of climate change by stating it was unusually cold that week. Of course, a day’s, week’s, or month’s temperature is an indication of weather, not climate. But his statements that day were consistent with his decades of anti-climate-change rhetoric, summarized in his book titled “The Greatest Hoax: How the Global Warming Conspiracy Threatens Your Future.” Of course, Senator Inhofe argued before Congress that he believed it arrogant of people and disrespectful to God to think that we humans could somehow affect the Earth. But perhaps the Senator was also swayed by the oil industry, too.

That summer, The Atlantic published a different kind of argument influenced by the oil industry. In “Why the Saudi’s Are Going Solar,” the reasoning for pursuing solar power was presented in terms of profits: Saudi Arabia makes greater profits by selling oil abroad than by using it to generate electricity domestically, so the Saudis are developing solar power for domestic electricity needs.

Fast forward to the summer of 2024 when The New York Times published another, different profit-driven explanation for Saudi Arabia’s investment in solar technology. In “Saudia Arabia Eyes a Future Beyond Oil," the kingdom is “betting that abundant, low-cost electric power could attract energy intensive industries like steel” and that Saudi Arabia’s solar-energy company is “helping to build what is likely to be the world’s largest plant for making [so called] green hydrogen, with an eye to exporting to Europe and other places with higher costs.”

Pervasive Ideologies

Although Senator Inhofe’s religious reasoning is easily identified as inflexibly ideological, capitalism’s ideology is so pervasive that its inflexibility often goes unnoticed: Of course any sustainable solution has to be more profitable than what it is replacing, right? But sustainability arguments that accept that inflexibility are doomed to argue on capitalism’s terms. For example, profitability arguments show up in a variety of ways in the technical support document of the U.S. EPA’s “Endangerment and Cause or Contribute Findings for Greenhouse Gases under Section 202(a) of the Clean Air Act.” As a result of capitalism’s pervasive ideology, scientists charged with the EPA mission ”to protect human health and the environment” report a kind of cost-benefit analysis in regards to such things as higher temperatures and increasing amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Higher temperatures on their own would reduce crop yields, they write, except for the “benefit” of increased amounts of carbon dioxide. More carbon dioxide will overall increase crop yields by as high as 9.2% for cotton. Of course, the scientists provided a caveat: “There is still uncertainty about the sensitivity of crop yields.”

Upon completing the overall cost-benefit analysis in December, 2009, then EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson concluded what’s now simply referred to as the Endangerment Finding: that the current and projected concentrations of the six key well-mixed greenhouse gases in the atmosphere “threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations.” In further clarification, the EPA webpage states, “these findings do not themselves impose any requirements on industry or other entities. However, this action was a prerequisite for implementing greenhouse gas emissions standards for vehicles and other sectors.”

Last week, the EPA’s recently confirmed administrator, Lee Zeldin, appears to have privately recommended that President Trump reverse course regarding the 2009 Endangerment Finding. In response, on Friday, February 28, 2025, the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works issued a letter to Zeldin again using the binding terms of capitalism’s ideology. They warned Zeldin of the “coming economic harms, which we see already presenting themselves in a property insurance—and increasingly unpredictable—crisis driven by increased flooding and wildfire risk.” In conclusion, the Committee wrote to Zeldin, “Your push to undermine the Endangerment Finding seems based not on sound science or legal reasoning, but rather on an agenda that prioritizes industry profits over public health, environmental protection, and climate safety.”

“All Equals None”: How SustainLab Will Frame Sustainability

At the most basic level, discussing sustainability requires the presupposition that it is important to discuss sustainability. That presupposition, in turn, may be used to derive “oughts,” such as we ought to clarify actionable approaches to sustainability and even we ought to act on those approaches. But just as ideas are culture- and language-bound, so there are people who do not believe it is important to discuss sustainability. Perhaps it’s because they prioritize their own religious understanding, industry profits, or political gain. But recognizing these other ideologies does not require the sustainability community to resist, employ, ignore, or worse, ridicule them. Rather, broadening the sustainability conversation requires the intellectual humility to be aware—and cautiously skeptical—of any ideology behind any “ought,” including any ought of a sustainability action, so that the sustainability discussion can include whether the “ought” is suitable within a culture or geography. Doing so will invite even more discussion—connecting the dots between researchers, policymakers, funders, and publics with varying understandings of disciplines, ideas, cultures, and political climates—to further clarify ideas and actionable approaches in ways that may become more suitable, or for which people in particular cultures or geographies should not waste further time. In sum, by naming ideologies inherent within any sustainability driven “ought,” the sustainability community can frame sustainability and actionable approaches in ways that are, in total, non-ideological, suitable to particular cultures and geographies, and do work to broaden the sustainability conversation.

That’s SustainLab’s goal: helping broaden that conversation by reporting on what’s working (and not working) in sustainability, sharing sustainability research and on-the-ground experiences, and reflecting on the scientific, economic, and political realities regarding humanity’s sustainable future. Whether you’re engaged in sustainability efforts or simply care about the world we’re leaving to future generations, I hope you’ll find ideas, connections, and purpose in SustainLab.

What prevents conversation about sustainability within your area of expertise—be it academic discipline, institutional setting, business, funding, policy, or something else?

I ask a lot of deliberately provocative questions to my students, but "Is capitalism is a religion?" is the one that most consistently raises their hackles.