Forecasting Forecasting

In uncertain times, "fauxstalgia" comforts. But making our world great (again?) means finding and filling the gaps between ideals and reality. Some researchers say A.I. must help.

In 1938, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster launched the character Superman in Action Comics #1. In it, the boy who would become Superman was an orphan from an unnamed planet. He didn’t get his powers or “funky high” from our yellow sun. Instead all of his planet’s “inhabitants’ physical structure was millions of years advanced of our own.”

At the time of Siegel and Shuster’s creation, the word “Superman” was in circulation because of a drama by George Bernard Shaw titled “Man and Superman.” Shaw intended the play as “a pretext for a propaganda of our own views of life.” One of those views of life was Nietzsche’s Übermensch (or “Superman,” though that translation of Übermensch was criticized much later — after Siegel and Shuster’s comics came out — with “Beyond man” or “Over man” preferred to avoid confusion). To Nietzsche, an Übermensch makes his own morality and values, and so is “a type of man that would be one of nature's rarest and luckiest strokes, as opposed to 'modern' men, 'good' men, Christians, and other nihilists.”

Hijacking Nietzsche’s philosophy, Adolf Hitler and the Nazis used it to justify racial superiority, although Hitler reportedly favored the philosopher Schopenhauer for glorifying “will over reason.”

As it happens, Siegel and Shuster were Jewish. They recast Superman — coming from a people “millions of years advanced of our own” (emphasis added) — as “Champion of the oppressed, the physical marvel who had sworn to devote his existence to helping those in need!”

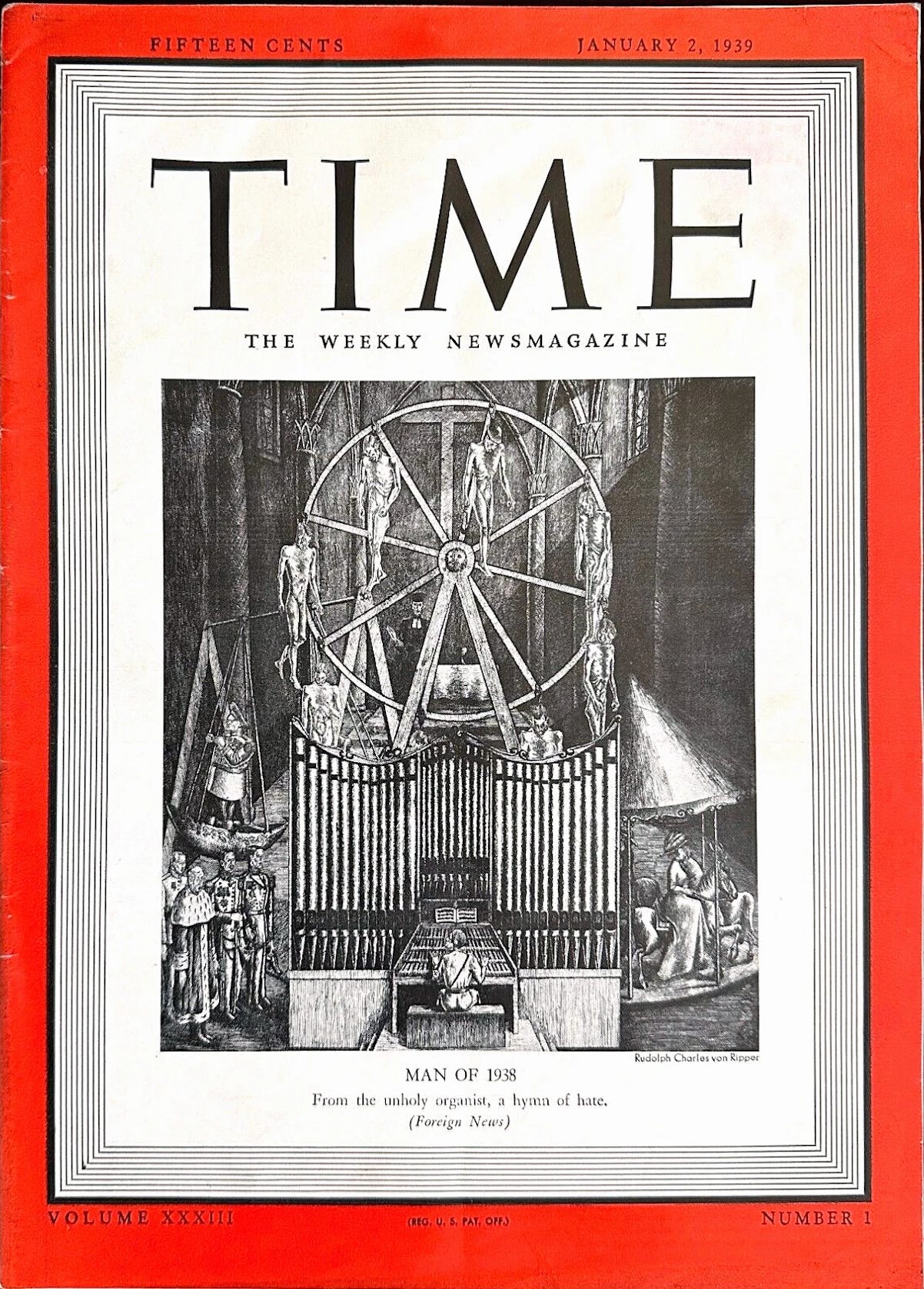

In 1938, much of the world desired such a champion. After all, Adolf Hitler was Time’s Man of 1938: “From the unholy organist, a hymn of hate” ran the caption beneath Time magazine’s cover depicting Hitler at the console.

Given the 1930s were awful — for many reasons — there are few people who look back at that decade with either nostalgia (for those who actually lived through it) or “fauxstalgia,” a portmanteau of “faux” (meaning “fake”) and “nostalgia.”

Making Our World Great

Today, though, there is a lot of fauxstalgia for the 1980s (see (1) (2) (3) easy examples). Coincidentally, the 1980s were a time when President Ronald Reagan was (also) saying “Let’s Make America Great Again” and conservatives generally were fauxstalgic for an imagined 1950s as a kind of comfort against the many problems at that time. In the U.S., problems in the 1980s included the Cold War, crack epidemic and gang violence, AIDS, and rising divorce rate. But making our world great means seeing clearly—without fauxstalgia for the past or hope for a future superman (of any variety, with or without a cape)—in order both to find and fill the gaps between our ideals and reality. Some researchers say Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) must play a central role in helping us with this process.

Narrowing and Broadening Gaps

Last week, the United Nations released its annual report on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) first adopted in 2015.

As Secretary-General António Guterres introduces the 2025 report:

Ten years since world leaders embraced the transformative 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, we have not only the opportunity but the obligation to take stock of progress, acknowledge shortfalls and act with urgency and responsibility.

Since 2015, millions have gained access to essential services. More than half the world’s population now benefits from some form of social protection, up by 10 percentage points compared to a decade ago. Child marriage and maternal and child mortality rates have fallen, and more young people, especially girls, complete school. Women now hold 27 per cent of parliamentary seats worldwide, up from 22 per cent. Access to electricity and clean cooking has expanded. Internet connectivity has increased by 70 per cent, opening new horizons. Around the world, young people, communities, civil society and local leaders are stepping up their action to deliver on the promise of the SDGs.

Despite these important gains, conflicts, climate chaos, geopolitical tensions and economic shocks continue to obstruct progress at the pace and scale needed to meet the 2030 target.

Only 35 per cent of SDG targets are on track or making moderate progress. Nearly half are moving too slowly and, alarmingly, 18 per cent are in reverse.

We face a global development emergency.

Over 800 million people are trapped in extreme poverty and hunger. Carbon dioxide levels are at the highest in over two million years, and 2024 was the hottest year on record, surpassing the 1.5°C threshold. Peace and security have worsened, with over 120 million people forced from their homes, more than double the number in 2015.

Meanwhile, debt servicing costs in low- and middle-income countries reached a record $1.4 trillion, squeezing resources needed for sustainable development.

-- excerpt from U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres introduction to The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025 published July 14, 2025 (emphasis added)Deploying A.I. To Help?

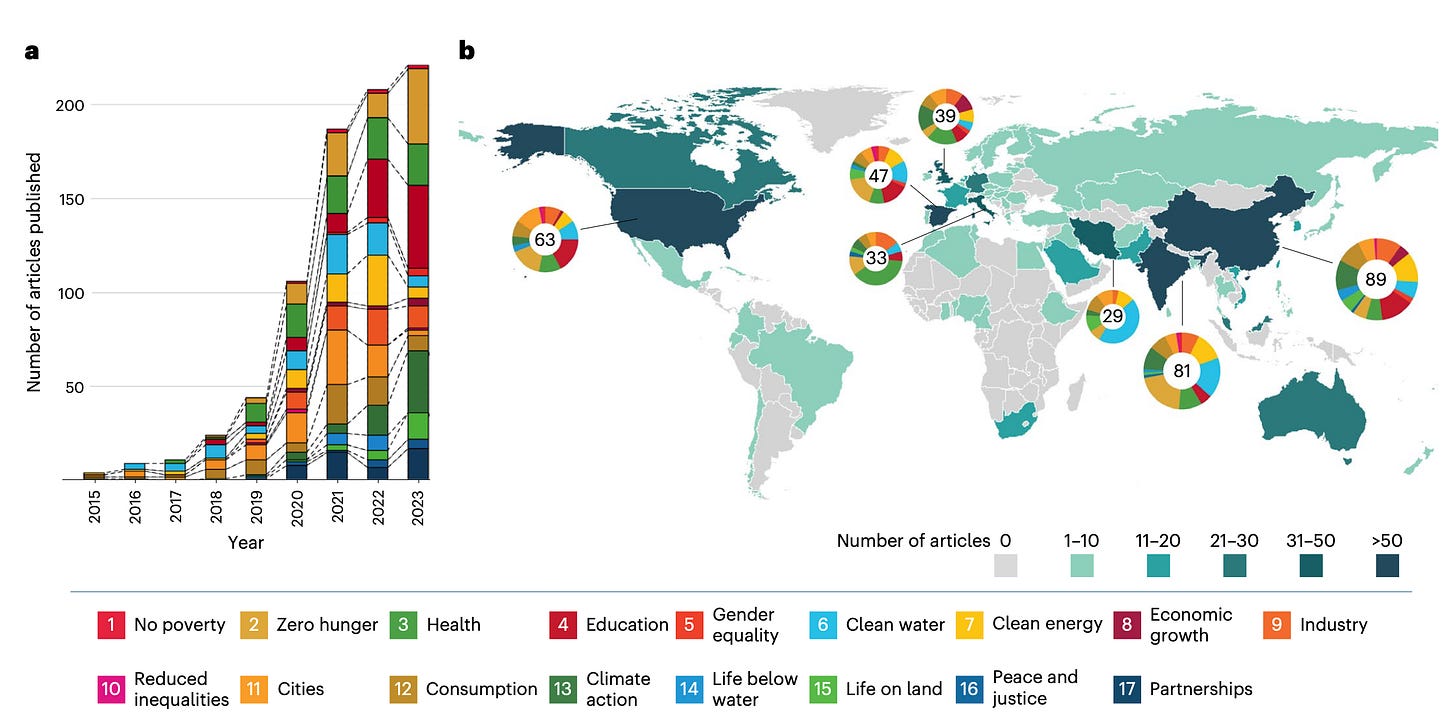

On Monday, Nature Sustainability published a study reviewing scientific articles that explore Artificial Intelligence (A.I.) applications in SDG-related research. The authors write in the abstract:

Sustainability needs to strike a balance between contextualization and generalizability to provide tangible knowledge that will lead to responsible change. A.I. must play a central role in this process. While expectations for A.I.’s transformative role in sustainable development are high, its full potential remains to be realized.

-- Gohr, C., Rodríguez, G., Belomestnykh, S. et al. Artificial intelligence in sustainable development research, published July 21, 2025 (emphasis added)The authors never argue why “A.I. must play a central role in this process.” But their meta-analysis of the full text of 792 research papers—ones that “met the inclusion criteria of engaging with both A.I. and one or several SDGs”—revealed a disconnect between A.I. methodologies and sustainability expertise.

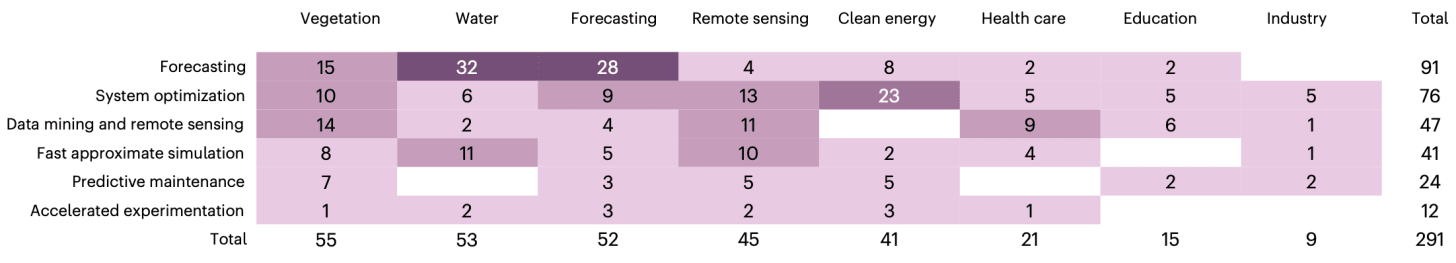

To make the disconnect obvious, the researchers generated heatmaps to illustrate where scientific research is concentrated, such as “forecasting - forecasting,” and where scientific research is largely absent, such as “predictive maintenance - healthcare.”

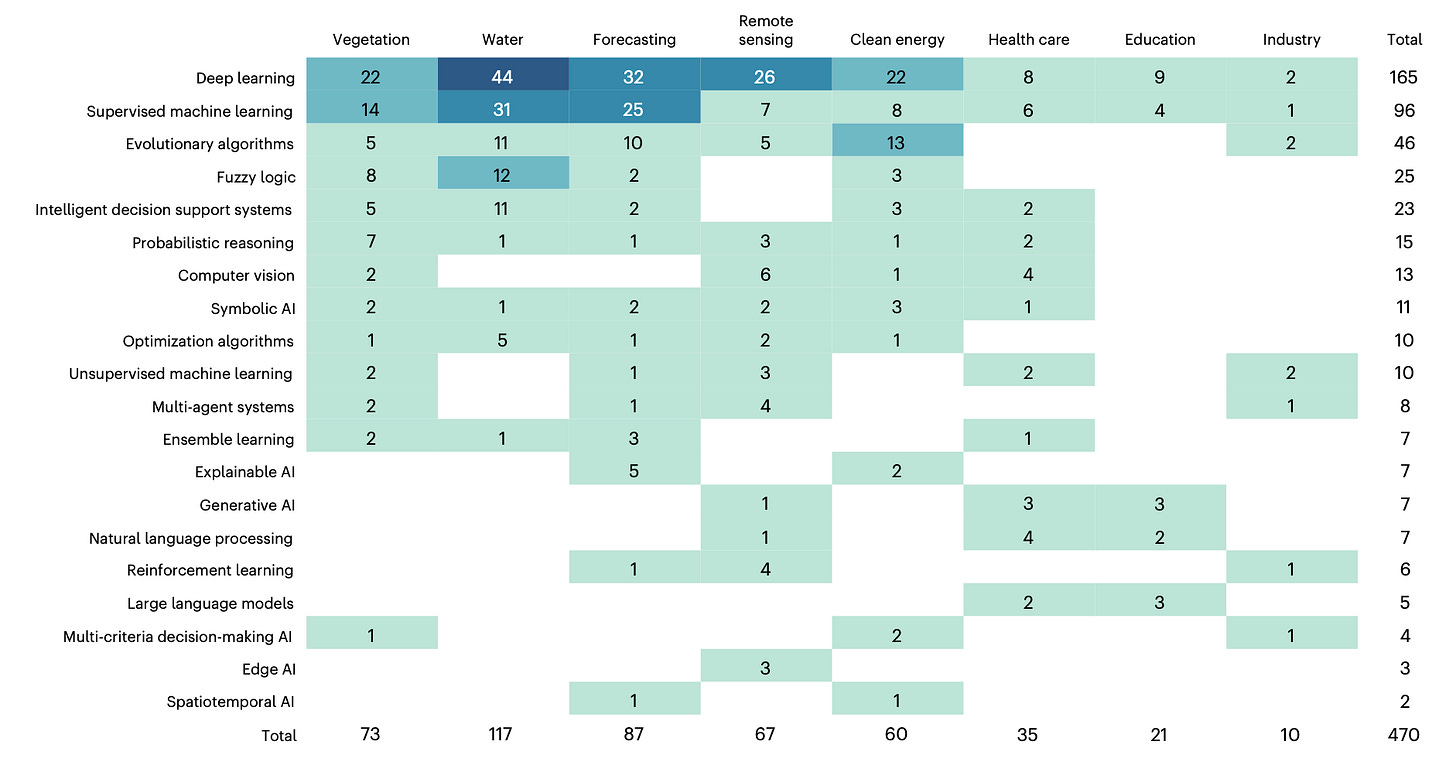

The authors also created a more detailed look at the top-20 most frequent A.I. algorithms employed by scientific researchers.

In their analysis, the authors report “choice of A.I. algorithms is strongly determined by the group-specific demands, challenges and data availability.” Those demands include geographic focus:

For example, studies from Iran, India and Spain focus on SDG 6 (clean water and sanitation), while studies from Italy and the United Kingdom predominantly address SDG 3 (good health and well-being). Articles focusing on SDG 4 (quality education) were most commonly published by authors in the United States, Spain and China. This variability in geographic focus is expected. As a reminder, the United Nations concluded there is no way to standardize sustainability in its 1987 World Commission on Environment and Development report titled “Our Common Future”:

No single blueprint of sustainability will be found, as economic and social systems and ecological conditions differ widely among countries. Each nation will have to work out its own concrete policy implications. But that there are zero studies — none that met the researcher’s inclusion criteria, anyway — that addressed any number of holes (white spaces in the heatmaps above) suggest that without such meta-analysis, scientists will not — on their own — employ A.I. to address the wider range of problems addressed by the U.N.’s SDGs.

“For example,” the researchers write, “A.I. is widely used in health, education and environmental modeling, but its use in poverty reduction (SDG 1) is minimal. We found only seven reviews and no empirical studies in the most cited literature applying A.I. to SDG 1 (no poverty).”

There are psychological reasons that fauxstalgia make sense. In an uncertain present we imagine a better past. So too are there psychological reasons to perceive a better future than present circumstances suggest, even pinning our hopes to a superman, real or imagined. But power alone — even in a tool like A.I. — does not guarantee progress. Indeed, Gohr et al expose a mismatch between A.I.’s promise and its deployment: use of A.I. proliferates in health, climate, and education modeling, but rarely to address poverty and social equity, and never in partnerships. A.I. may one day help us close those most persistent gaps between the future we imagine and the world we create. But we have to decide to use A.I. to help us close those gaps, first.

For more about A.I. on SustainLab, read “Nuclear-Powered Search.”

To what extent are we — as individuals and communities — responsible for steering A.I.’s use, and what practical roles can we play in that process?

My new favorite word, "fauxstalgia!" Thank you for a thought provoking informative article.