Can "More or Less" Thinking Save Our Future?

Move beyond binary choices of "sustainable or not" to take a pragmatic approach to Do Something.

In an uncertain world of dangers and perils, we are compelled to seek certainty and safety. Our ancestors used two methods to attain certainty and safety—two methods we still employ today—changing ourselves and changing the world.

In changing ourselves, ultimately we seek to overcome concerns with uncertainty or safety. We might adopt habits and rituals to appease supernatural forces we do not understand or try to accept uncertainty, danger, and perils as inherent to life.

In changing the world, ultimately we seek to remove the dangers and perils and replace uncertainty with certainty. We might build ourselves fortresses, attempt to dominate nature, or live in such a way as to leave nothing to chance.

The above is my takeaway from John Dewey’s sweeping sketch of humanity’s two historical paths from his 1929 Gifford Lectures, which was published as “The Quest for Certainty: A Study of the Relation of Knowledge and Action.” Dewey’s contemporaries immediately criticized it as, among other things, “a little too simple.”

But many of Dewey’s so-called “simple” ideas caught on and are still in use today. For example, Dewey was also known for his pragmatism, including the educational technique simply summarized as learning by doing.

Yes, the title of this post — with “More or Less” Thinking — was absolutely designed to get attention. I have come to understand people will stop and look more deeply at what they perceive are mistakes. This kind of attention-seeking title-making is something I am “learning by doing.”

Whether changing ourselves, changing the world, or changing both, Dewey’s “a little too simple” idea about humanity’s quest involves doing something — a particularly appealing idea to young people. Indeed, for many youth around the world, “do something” refers to an organization (founded 1993) that for decades has engaged millions of youth in “building a better world.”

Today, though, even “do something” often translates into “buy something.” Indeed, financial records from the Do Something non-profit shows income from the organization’s DoSomething Strategic consultancy supporting the non-profit by helping “clients engage the next generation for good”:

From the gut check on key decisions to crafting new pathways for cause marketing, consumer loyalty, and member engagement—we are a trusted thought partner for leadership across sectors and industries.

It’s unfortunate, but this translation from “do something” to “buy something” happens so often because of the “almost irresistible pressure” of the market to remodel “every institution in its own image,” as Christopher Lasch put it.

The market notoriously tends to universalize itself. It does not easily coexist with institutions that operate according to principles antithetical to itself: schools and universities, newspapers and magazines, charities, families. Sooner or later the market tends to absorb them all. It puts an almost irresistible pressure on every activity to justify itself in the only terms it recognizes: to become a business proposition, to pay its own way, to show black ink on the bottom line. It turns news into entertainment, scholarship into professional careerism, social work into the scientific management of poverty. Inexorably, it remodels every institution in its own image.

— Christopher Lasch, The Revolt of the Elites (1995), [emphasis added]

To Lasch’s list of “institutions that operate according to principals antithetical” to the market, please allow me to add the United Nations—or really any institution focused on sustainability. The U.N. also “does not easily coexist” with the market, at least not the free market, which tends to ignore costs to environmental effects, social systems, and business operations.

That said, the market has tried—and keeps trying—to incorporate such costs through Environmental, Social, and Governance (E.S.G.) investing metrics (often independently defined by companies — here’s I.B.M’s) because an increasing number of investors are recognizing the importance of sustainability to our shared future. Citizens, too, are demanding sustainability from their governments. And those governments in the Global South (BRICS) and European Union, among others (e.g., Japan) are at least trying to incorporate E.S.G.-related regulations into corporate, trade, and finance policies. E.S.G. and sustainability are not the same as financial investment houses readily admit, and E.S.G. also suffers from a “lack of uniform criteria and a common market standard for the assessment and classification of financial services and financial products as sustainable.” But again, as aforementioned, markets and governments are trying to “do something” at least insofar as it still makes sense to those focused on the bottom line.

So what to do sustainability-wise in a world that prefers simplicity — whether sustainability is driven by market forces or by humanity’s compulsion to seek certainty and safety in an uncertain world of dangers and perils, such as climate change?

First, let me say that it is going to take some individual and community-based work because the characteristics of sustainability are unique to your habitat. But what we can all do is avoid binary characterizations: “right or wrong,” “certain or uncertain,” “safe or unsafe,” “sustainable or unsustainable.” Like the aforementioned critique of Dewey, these binary characterizations are “a little too simple.” They do not recognize sustainability as a spectrum, one that is better characterized by “more or less.” The more or less framework underlies the U.N.’s Paris Agreement. The more or less framework also makes it easier to compare sustainability actions — and doing something — rather than try to term an action “sustainable,” which can feel like an impossible task when you try to calculate all the inputs and outputs. So, for example — using a list I provided in a previous SustainLab post — taking one less transatlantic flight per year is more sustainable in terms of climate impact than, say, carpooling for a year; comprehensively recycling is less sustainable in terms of climate impact than shifting to a lower-carbon meat or vegetarian meal.

Localize the spectrum: What is more or less sustainable in your habitat —whether your habitat is your culture, economy, political environment, and/or geography — may not be more or less sustainable in mine. For a majority of people where I live, for example, it is meaningless to talk with them about “taking one less transatlantic flight per year” because they do not take any transatlantic flights at all. But what I can talk about with my neighbors is how much they play with energy-intensive Artificial Intelligence.

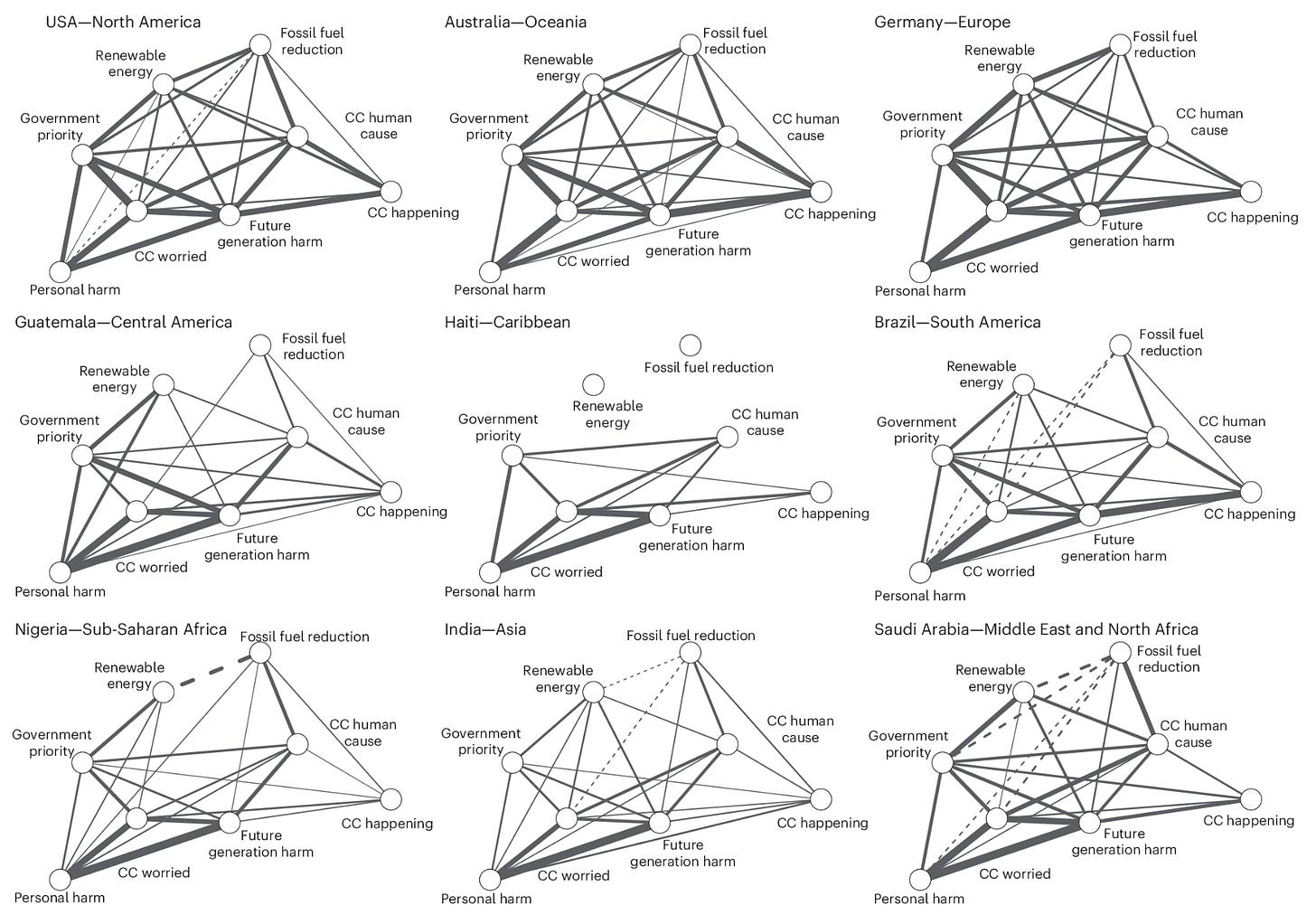

Then discuss/model/argue the localized spectrum: There’s nothing like an argument to encourage people to become familiar with factual information. But an argument does not have to be combative: modeling more sustainable behaviors (e.g., bicycling to the local coffee shop instead of driving a car there) makes an argument all its own. In situations where modeling may not make sense (including online communities), arguing the “more or less” spectrum can help everyone (you, too!) clarify and articulate the dilemmas people face in working to address sustainability challenges together. For example, researchers recently reported a negative correlation in the U.S.A. between “personal harm” and “fossil fuel reduction” (shown by a dashed line in the graphic below, top left diagram). That, in turn, “create[s] challenges due to potential resistance to interventions” such as requiring higher fuel-efficient cars. In other words, many people in the U.S.A. recognize the importance of prioritizing climate policies but they still resist fossil-fuel-reduction interventions because it threatens their economic stability.

What is sustainable changes with culture, economy, political environment, and geography. It also changes with time. So, going forward, rather than asking — or arguing about — whether an action is sustainable, consider evaluating instead how much better or worse each choice in actions is for our shared future.

Discussing sustainability’s spectrum, modeling more sustainable behaviors, and debating sustainability trade-offs encourages nuanced thinking and community-mindedness. It also transforms abstract goals such as “be sustainable” into “do something” steps: one fewer flight, one more vegetarian meal per day, one more quick trip on a bicycle instead of in a car. With each step, we become a little more certain, a little safer, and maybe even a little more hopeful about our shared future.

In your field, expertise, or habitat, how to you move from acknowledging sustainability challenges to navigating toward sustainable practices? Have you tried open-ended, inclusive questions that prompt reflection and dialogue such as “How can we come together to improve this sustainability practice or make what we do even more sustainable”?

I am reminded of the Chinese proverb, "A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step." Your advice on being curious and asking how we can work together to solve an issue works in many different venues, including sustainability.